Héctor Abad Faciolince: "I'm one of the cowards who survive." The writer talks about "Now and in the Hour"

Héctor Abad Faciolince experienced firsthand the horrors of the war in Ukraine when a Russian missile hit the restaurant where he was. The attack killed one of his table companions, the writer Victoria Amelina, and left him with several mental injuries that led him to take antidepressants. This is the story of his new book, Ahora y en la Hora (Now and in the Hour).

On June 27, 2023, hundreds more people fell victim to a Russian attack in the city of Kramatorsk, Ukraine. A missile fell on a restaurant where some civilians were trying to continue their lives in the midst of the war. However, at 7:28 p.m., the lives of all these people, including Colombian writer Héctor Abad Faciolince, changed forever, as he captured in his new book, *Ahora y en la hora*: “In that hell that fell on us from the sky with the deliberate purpose of causing as much damage as possible, of producing as many deaths as possible, of causing the greatest possible pain and suffering, there were more than sixty seriously injured (some maimed for life) and twelve human beings killed instantly, among them two fourteen-year-old twin girls, Juliya and Anna Aksenchenko.”

Héctor Abad Faciolince presented "Now and the Hour" at the Filbo. Photo: Getty Images

That attack marked his life forever, or as his wife later told him: "It would screw up their lives forever." His participation in a book fair ended in tragedy. Because beyond the physical wounds, what the Iskander missile's shrapnel left in Héctor Abad were deep emotional wounds. And these are what the reader of Now and in the Hour can feel on every page. In it, he tries to understand "what happened to him and what changed in him after the Russian attack?" From there, he eventually says: "I think, in reality, that I write so I don't die and to understand and deserve death."

This is how the restaurant in Kramatorsk looked after the Russian attack. Photo: Genya Savilov

Writing this book was more difficult than ever before in his life. Something had broken, and the words seemed to slip through his fingers. Guilt, fear, depression, and sadness seemed to push him ever deeper into silence. But forgetting was impossible because what happened to him that day wasn't just part of his story. Now and in the Hour is also a tribute and a long love letter to those companions and friends with whom he undertook the journey through Ukraine. Among them were Sergio Jaramillo, former negotiator of the peace agreement with the FARC and representative of the ¡Aguanta Ucrania! movement, which sought support in Latin America for the Ukrainian cause; Catalina Gómez Ángel, the Colombian journalist who had been covering the war in Ukraine for over a year; Dima, their guide in Ukraine and in charge of transporting them around the country, and Victoria Amelina, a writer and activist who put aside her literary career to dedicate herself to documenting the crimes of the Russian invasion, but who died on the day of the Russian missile attack: “I became Victoria's friend after her death. Not before; I didn't know her well enough. But I love her like a close friend even after her death,” says Héctor Abad.

Sergio Jaramillo and Héctor Abad Faciolince. Photo: Private archive

It is in their honor and in Amelina's memory that she was compelled to write this account of what is happening in Ukraine and how that close encounter with death changed her life. However, writing Now and in the Hour was fraught with challenges and heartache.

You tried to explain what happened to you in Ukraine through fiction. At what point did you feel that this wasn't the way to understand, or make comprehensible, what had happened to you?

Yes, actually, ever since I started writing—a friend of mine noticed this—I always write two books at the same time. One more based on memory, testimony, and experience, and the other more based on imagination. In this case, that was taken to the extreme, because I wrote two books at the same time, and what's more, they were two intertwined books. One was a pure novel about an old man who goes to the Gaza border and tries to smuggle food from Egypt, because people are starving to death inside. One chapter was that novel, and the other chapter was a bit of the testimony that finally appeared in Ahora y en la Hora (Now and in the Hour). I really didn't know what to do, and I didn't know which of the two stories, the imaginary one or the testimonial, would be published. What happened was that I had to deliver the book at the end of 2024, and on December 29th, my first grandchildren, twins, were born prematurely. It was a very rushed and horrible thing to do, because while they were in the ICU, I had to deliver the book, and I didn't know how to finish it or anything. So, I sent the book to my editors, one in Spain and one in Colombia. It consisted of 13 chapters of fiction and 13 chapters of testimony. Then I told them: "I'm in this situation of happiness and anguish at the same time for these twins, and I don't know what to do. Please help me."

And were they the ones who found the solution?

They decided, especially Carolina López, to eliminate the entire fictional section, to steal some paragraphs from the fiction. That's why you can see that there are elements of fiction in the book, but what emerged was basically the chronicle, the book of testimony about Ukraine. The book about Gaza disappeared. I completely agreed. Furthermore, they did a very important editing job, because the book wasn't assembled exactly as it reads today. They gave it this final form.

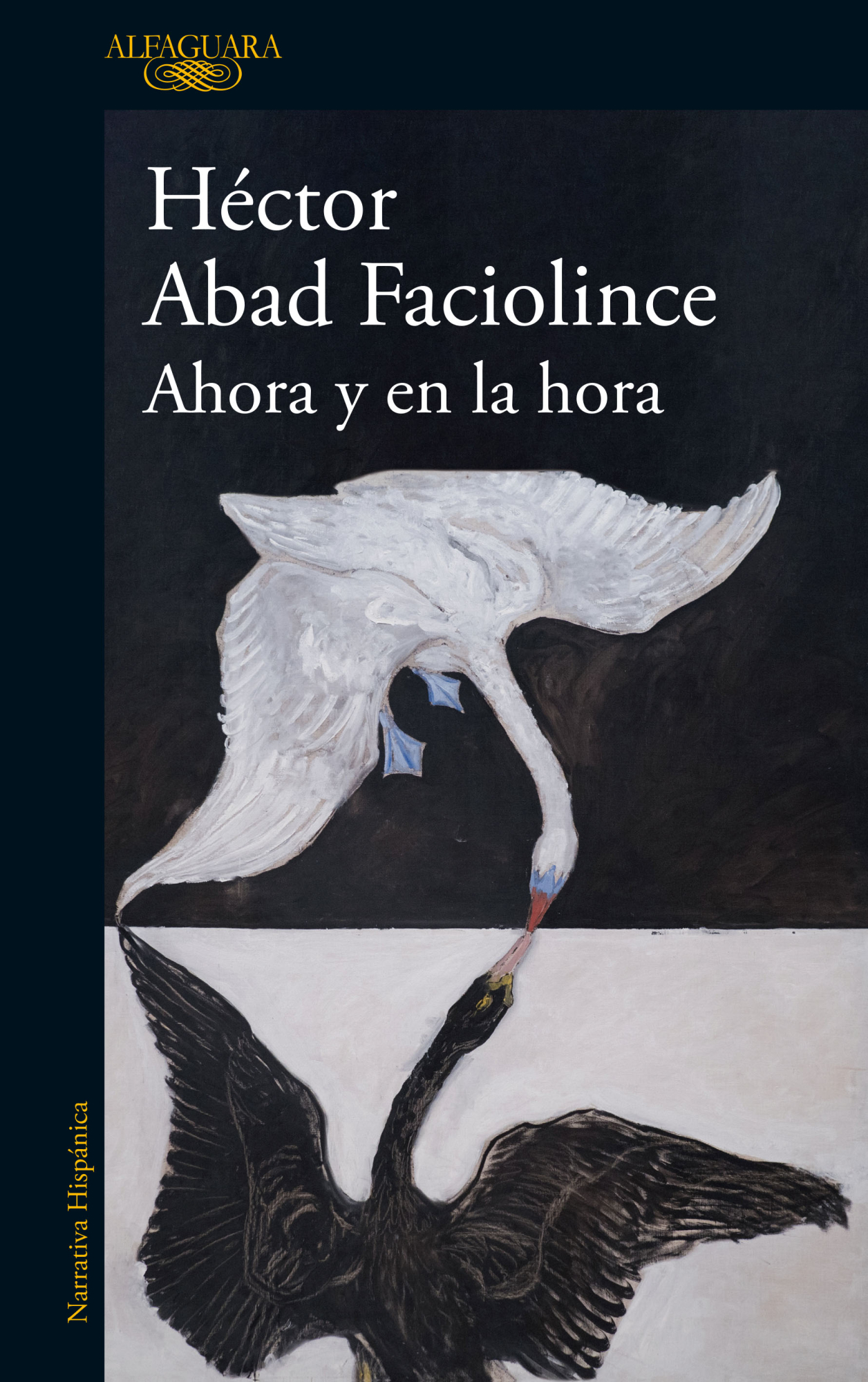

Now and in the hour, Héctor Abad Facolince, Alfaguara Photo: Private archive

“My dearest ally, always, is forgetting,” you say in your book. And it's true that the word forgetting—and what it can mean—is very present in your work. But how do you address this tension between forgetting as a survival mechanism and the need not to forget as a mechanism of resistance, justice, and truth?

There was tremendous tension while writing the book, because on the one hand, I wanted to abandon myself to what I'm an expert at: forgetting, and at the same time, I couldn't allow myself to forget. Because for me, it was very important to leave Victoria's testimony, the testimony of what her life had been like, the testimony of what she was doing, and the testimony of her unjust death. Only I didn't want to stay, like I choked on the story of my father or my sister, for example, for many years, for decades. I had to regurgitate all of that quickly so I could dedicate myself to what I'm dedicated to. Let's say I know I won't forget everything completely, but I do know I won't be wrapped up in the details, that I won't have to continue having nightmares and ideas, and I won't have to feel the obligation to remember everything as precisely as possible in order to be able to write it down as precisely as possible. As if everything is already in the book, and a book or writing, as Borges always said, is a support for memory. The responsibility no longer falls on my mind. It's already there, and then I'm calmer. I don't feel that duty, that obligation, that responsibility I felt. And well, if I forget, although I won't forget everything, it doesn't matter anymore. I've fulfilled my duty to remember.

You've said that when you wrote this book, words seemed to elude you, so elusive that your language seemed to crumble as you recalled the events at Kramatorsk. Why do you think this happened?

Yes, I had, or felt, a physical resistance to writing this book. I felt like I wasn't capable. That for the first time in my life, I wasn't able to write what I wanted, what I felt like. I felt like the words weren't flowing. This is also because I had to start taking antidepressants because I was really bad. And I think the psychiatric drugs themselves didn't allow me to concentrate on the pain. I imagine that antidepressant drugs prevent one from concentrating on the pain in order to heal it, but I needed to concentrate on the pain to write it. It was like an internal struggle between the mental state necessary to be able to write something painful and the mental state impeded by what was happening to me, by my depression. At the same time, I thought, "I must be losing my faculties already." So I also went and took a cognitive test to find out if I was really being scared, if I was really... For example, my editors have always played a very important role in my books, but I've always finished them until the last minute. To be honest, I wouldn't have been able to finish this book of mine on my own. I owe a lot of it to Carolina López.

In the book, there are several parallels with The Oblivion We Will Be. For example, you write: “I am the same age, sixty-five, as my father was when he was killed.” However, at the end of the book, you state: “If I have concluded anything upon returning from Ukraine, it is that I will never again want to die like the hero my father was, not even for a just cause.” What do you think about this figure of the hero in our time?

What's in a name? Shakespeare wrote. Let's say there's a hero par excellence in the great primordial tale of war, the Iliad: Hector. He knows he's going to face a demigod, Achilles. He knows he's going to be killed, but he goes into battle because it's what he has to do for Troy, for his people, for his son, for his father, for his wife, and he gets himself killed. And my father got himself killed. I've always quoted a verse by Quevedo that says: "A coward with a brave name" to define myself, a coward with a brave name, not only because of my father, but because the name Hector is a typical name for a heroic warrior. Victoria Amelina, in her posthumous book, Looking at Women Who Look at War, says at one point that she believes she could be killed at any moment and that she writes that book hoping that her son will one day read it and understand and forgive her. And she's a woman. Most heroes are traditionally men; Ukrainian women flee with their children to the West, they escape. In Victoria's case, she stays, sends her son to Poland, and her husband lives in the United States. She's a heroic woman who stays. So, that figure of the heroine in this case is very powerful for me. Also, because I also mention it a lot in the book, she was the same age as my daughter. And imagining, I'm already old, unfit for war, that my daughter would have to dedicate herself heroically, not to taking care of her children, but to denouncing the war crimes of those who had just invaded us, made me despair... something indescribable. The most tragic countries are those where there's a need for heroes, where someone's ability to sacrifice themselves for a just cause is evident and one understands it, that one admires it, and that it's even a beautiful way to die, doesn't mean that it's desirable. One wishes for a world where heroes weren't necessary. It's very difficult to live with heroism. It's something one admires, appreciates, and loves very much, but when the hero has a family, it leaves a personal devastation that makes one doubt whether it was worth it. And yet, there are things one cannot renounce. That is, if one is going to be humiliated, if one is going to have all one's freedoms taken away, if one's children or parents are killed, then it's understandable that one would want to get killed.

In this book, Héctor Abad discusses the figure of the hero and cowardice. Photo: MAURICIO MORENO

You say: "I'm not writing this book, then, to feel brave, much less to put on the hypocritical mask of a good citizen who risks his life for a just cause. I'm writing it to confirm my cowardice." The cowardice that has always haunted you, like a kind of stone tied to your body. Why do you think we cowards always feel judged?

It's just that being a coward is ugly. I mean... I once spoke and supposedly gave a very brave speech at the Medellín City Council after they killed my father. A speech where I declared myself defeated and I don't know what. I was there with my mom and we left the City Council and it was already nightfall. After that, everyone who spoke that day was killed. Everyone, except me. But that day, when my mom and I left and said, "Well, we're all right now, we're at least out of this," two young, bald guys came along, carrying a backpack and reaching inside it, and they came at us. My mom stood in front of me and opened her arms and said, "Not him, not him, not him." And the guys kept going. But the incredible thing is that I let my mom stand in front of me. I let my mom be my shield and not me, a 27-year-old guy, my mom's shield. That she was the brave one and I the coward. That's very nice of her, that she stood up for herself, that she, with her old age and her voice, I believe, scared them off. It's beautiful. But what if they had shot her and killed her, but not me? It's an unacceptable thing, a shameful thing. And so it was, that I played the role of coward so many times in my life.

Catalina Gómez, Colombian journalist. Photo: Private archive

Something that happened to him again in Ukraine.

Let's just say I didn't want to go to Ukraine. I was the coward. I went out of lack of character, because a negotiation expert convinced me, because Catherine said, "If you're scared, don't worry, we'll never go." And I felt sorry for her. I said to myself, "They're going to realize once again that I'm the coward here." And I said, "No, let's go." Maybe they won't kill us, maybe nothing will happen. But that stayed with me in a very horrible way. So much so that sometimes I had a crazy fantasy that I had indeed died there, but I hadn't realized I was dead and that I had gotten up, and I thought life went on as usual, but in reality I had died, I was dead. Well, anyway, after episodes like that, one has very crazy thoughts. And of course, cowardice is also an instinct for self-preservation. But of course, in Ukraine, I was the oldest person at the table. I was happy to have survived, but at the same time, I felt very guilty about having survived and the deaths of children there, these two twin girls, and Victoria. Happy to have survived, but also horrified to have survived, like I don't deserve it. I'm one of the cowards who survive, not one of the brave ones who get killed.

Throughout your retelling of your story in Ukraine, one feeling occasionally surfaces: hatred. Did you feel that feeling when you were writing this book?

Yes, there were times when I... My editors deleted, let's say, a chapter of hatred; and I think they were right to delete it. A chapter in which I talked about a general who took off his hat and toasted those who had carried out such a brilliant military operation as the one at the pizzeria in Kramatorsk. I don't remember the general's name, but it was there. Or I remembered what the Russian ambassador here said when he mocked us by saying it wasn't a good idea to go and taste typical dishes in Ukraine. I also mentioned some colleagues who said afterward: "There's Héctor Abad with his clothes covered in shit," or that that missile was legitimate because the second floor of that restaurant housed NATO offices, and that restaurant didn't even have a second floor. In short, there was a chapter, if not of hatred, then of great resentment. The greatest resentment, and which hasn't been fully edited, is against Putin, who seems to me to be the incarnation of evil. I believe, and this is from Borges, that to hate is to remember those who deserve to be forgotten. And I believe that forgetting is the only revenge and the only forgiveness; this is also from Borges. I don't live thinking about revenge for those who killed my father here. No, I hope they die of old age; if they haven't already. I don't care anymore. I don't remember them. They're not in my head.

Ukrainian writer Victoria Amelina died in the Russian attack. Photo: Private archive

Victoria Amelina is a key character in your story in Ukraine. In some passages, you compare her to a swan. What do you still remember about her? What questions do you still have?

I didn't even discover the swan thing; my wife, Alexandra, saw it. For me, the swan is loaded with a very strong symbolism of fragility and beauty. Swans seem very arrogant, very nonchalant, with their high necks, looking down at them. Victoria kept saying, "What's going to happen to me? What could happen to me?" As if she were truly strong. The whole thing about the swan was meant to speak to the force with which Victoria was denouncing, from her own point of view and that of Ukrainian women, what was happening. That civic courage of abandoning the novel, abandoning children's stories, and dedicating herself solely to meticulously documenting Russia's war crimes, following very precise rules. It's an astonishing act of courage. She goes to the front lines again and again to visit soldiers, to visit the families of the dead, to visit the families of the children kidnapped and stolen by the Russians. So, yes, with a haughtiness, with a strength, with a tranquility as if nothing were really going to happen to her. She was as fragile as any white swan dressed in black. That's why I also quote her poems because she says that during the war, the only literary genre, outside of documenting war crimes, that was available to her was poetry, because it exploded. Poetry explodes into verses like shrapnel from a bomb or a grenade. So she channeled her indignation, her anger, her pain, her rage through poems.

After everything that's happened and continues to happen in Ukraine, how difficult it was to write this book, and how complex it was to understand the aftermath of the attack, do you have any optimism for the future?

One is too small to influence the things that happen. One is nothing, and one must be very aware of that. The future of the world is not in our hands. Let's say there are some very powerful people who may have in their hands, not the future of the world, but they can make decisions that greatly affect the present and future of the world. Donald Trump, Putin, the great leaders of the world could prevent a lot of deaths and massacres. But since we don't have that role, and neither do writers, the only thing we can do is write something about what happens. There's an old conclusion from the most pessimistic of writers, who was nevertheless a very joyful man and wrote with great joy: Voltaire. He said: "We have to cultivate our garden." The garden I most want to cultivate is that of writing and that of my intimate and family life. We know nothing about the future, but to deserve death, I believe we must lovingly cultivate the garden that belongs to us, because that is what allows us to leave a good memory.

You say your wife, Alexandra, has told you several times that your trip to Ukraine ruined their lives forever. Do you think that's true?

I think it did screw up our lives, but fortunately, not forever. I think time, and in part forgiveness, new experiences, and the fact that life goes on mean that even the most horrific things aren't eternal. Instead, there's a moment when the most horrific things can begin to dissolve, like death dissolves into new lives, fortunately. And that allows one to move forward with courage and hope.

Recommended: Freda Sargent's story

The garden is one of Freda Sargent's major themes. Photo: Sebastián Jaramillo / BOCAS Magazine

eltiempo

%3Aformat(jpg)%3Aquality(99)%3Awatermark(f.elconfidencial.com%2Ffile%2Fbae%2Feea%2Ffde%2Fbaeeeafde1b3229287b0c008f7602058.png%2C0%2C275%2C1)%2Ff.elconfidencial.com%2Foriginal%2Fb0a%2Faa2%2F6e6%2Fb0aaa26e626c1010324aec887eec8b1f.jpg&w=1280&q=100)

%3Aformat(jpg)%3Aquality(99)%3Awatermark(f.elconfidencial.com%2Ffile%2Fbae%2Feea%2Ffde%2Fbaeeeafde1b3229287b0c008f7602058.png%2C0%2C275%2C1)%2Ff.elconfidencial.com%2Foriginal%2Fc38%2Fe3e%2Fffd%2Fc38e3effd3f522e20c1d3a5ea879598e.jpg&w=1280&q=100)